Knee ligament injuries as a result of trauma can result in significant pain and joint instability, these knee injuries can impact on everyday life and sporting activity.

When managed effectively with simple strategies and expert advice it is usually possible to make a full return to previous levels of work and activity.

What is a knee ligament?

Ligaments can be found all over the body and essentially are soft tissue (flexible connective tissue) structures which connect bone to bone, in this case the thigh bone (femur) to the shin bone (Tibia) and small shin bone (Fibula).

The role of knee ligaments is to provide stability to the knee joint; without stable and functioning knee ligaments to control rotation, our knee would feel wobbly and unstable whilst carrying out the most basic of human movements let alone when subjected to the demands of physical activity and sport – put simply, ligaments connect bones.

This is another reason that knee ligament injury is one of the most common sports injuries presenting to GP’s, Physiotherapists, Orthopaedic Surgeons and Sport and Exercise medicine consultants usually following a twisting knee injury, hyper-flexion or hyperextension.

What are the knee ligaments called?

There are 4 major ligaments in the knee that are commonly mentioned and sustain the majority of injuries. In truth there are many more soft tissue structures such as the patellar tendon which contribute to the overall stability of the knee joint and these will be mentioned later but to begin with we will focus on the common ligaments.

ACL – Anterior cruciate ligament

PCL – Posterior cruciate ligament

LCL – Lateral collateral ligament

MCL – Medial collateral ligament

ACL Injuries – Anterior Cruciate Ligament

ACL injuries as part of complex knee injury occur due to a rapid rotational, hyperextension or deceleration mechanism of injury with associated valgus forces through the knee. Whilst ACL tears share many aspects in terms of the mechanism of injury (how it occurs) the truth is each injury is likely to be unique and associated with specific additional soft tissue injuries to other ligaments and meniscus. We wrote a previous blog on Complex Knee Injuries and why no two injuries are the same.

ACL injuries are very common in change of direction sports such as Football (soccer), Rugby, NFL, AFL and Basketball or when playing Hockey or Netball, but can also occur with non-sporting activity if the rotational forces and lack of muscular strength combine to put the knee in a vulnerable position.

I’ve injured my ACL – now what?

At the moment of ACL tear there is likely to be significant pain and swelling. The joint stability is likely to be reduced and the knee may feel like it wants to give way as the structure which controls rotation is injured. The swelling inside the joint (Haemarthrosis) is usually large and will result in loss of range of motion within 12-24 hours. It is important to manage the injury effectively in the immediate aftermath with ice to reduce pain and compression to reduce swelling, a brace may be fitted if you have access to immediate spots medicine care and you are likely to be give crutches.

It is important you are formally assessed and have you knee ligament injury diagnosed by a musculoskeletal specialist. Diagnosis can usually be made by accurate history, viewing of the mechanism (if available) clinical assessment and specific ACL orthopaedic tests such as Lachman and Anterior Draw Tests, demonstrating knee joint instability secondary to ligament laxity.

Lachman Test

Anterior Draw Test

Professional football player Rob Holding discusses his experience of ACL injury and his immediate feelings in the video below.

An MRI scan is needed to visualise the structures on the inside of the knee and complete the diagnosis. At this point a decision will be made on the necessity for surgical reconstruction or conservative rehabilitation.

On some occasions the complexity of the ligament injury and associated structural involvement my make surgery the only option but in the majority of cases a discussion can be had and decision made about what you want to return to in life and a decision made about which path to take – it is important to state that increasingly the evidence is showing that people can recover fully from ACL injury without the need for surgery, though in high level sport and rotational activity it remains the case that the vast majority of injuries are treated with reconstructive surgery and a rehabilitation program of 9-12 months.

Have a read about the knee rehabilitation process at R4P here.

Complex Knee ligament injury

As mentioned above in recent years we have started to refer to ACL injury as “Complex knee injury including ACL” due to the huge variety in types of these injuries. It is no exaggeration to suggest that no two complex knee ligament injuries are the same in the future it is vital we further sub-group these injuries to enable a better diagnosis and prognosis process.

Firstly its important to state that any musculoskeletal injury is a unique experience. The individual will have characteristics in terms of soft tissue type (eg hyper-mobility), age, pain and swelling response; and that’s before the collective injuries can be considered. An ACL injury is likely to have at least one associated soft tissue knee injury. This could include:

Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL injury)

Lateral collateral ligament (LCL injury)

Medial collateral ligament (MCL injury)

Medial Meniscus

Lateral Meniscus

Capsular Injury (Ramp lesion)

Posterolateral corner (PLC injury) which can include injuries to any of the PLC structures such as Lateral or Fibula collateral ligament, Popliteus Tendon, Popliteofibular ligament, Meniscofibular ligament, Meniscotibia ligament, Fabellofibular ligament, Arcuate Ligament, Lateral head of gastroc, Distal Biceps Femoris tendon, Illiotibial band (ITB), Proximal Tibiofibular joint. That list of structures alone gives you a good idea why it is far too simplistic and reductionist to just group ACL injuries as one. Read more about them here https://rehab4performance.com/posterolateral-corner-knee-injuries/

PCL Injuries – Posterior Cruciate Ligament

Although injured less often than the ACL the knee does have a second cruciate ligament. The PCL sits at the back of the knee (posterior meaning towards the back) and works in conjunction with ACL to provide rotational stability for the knee.

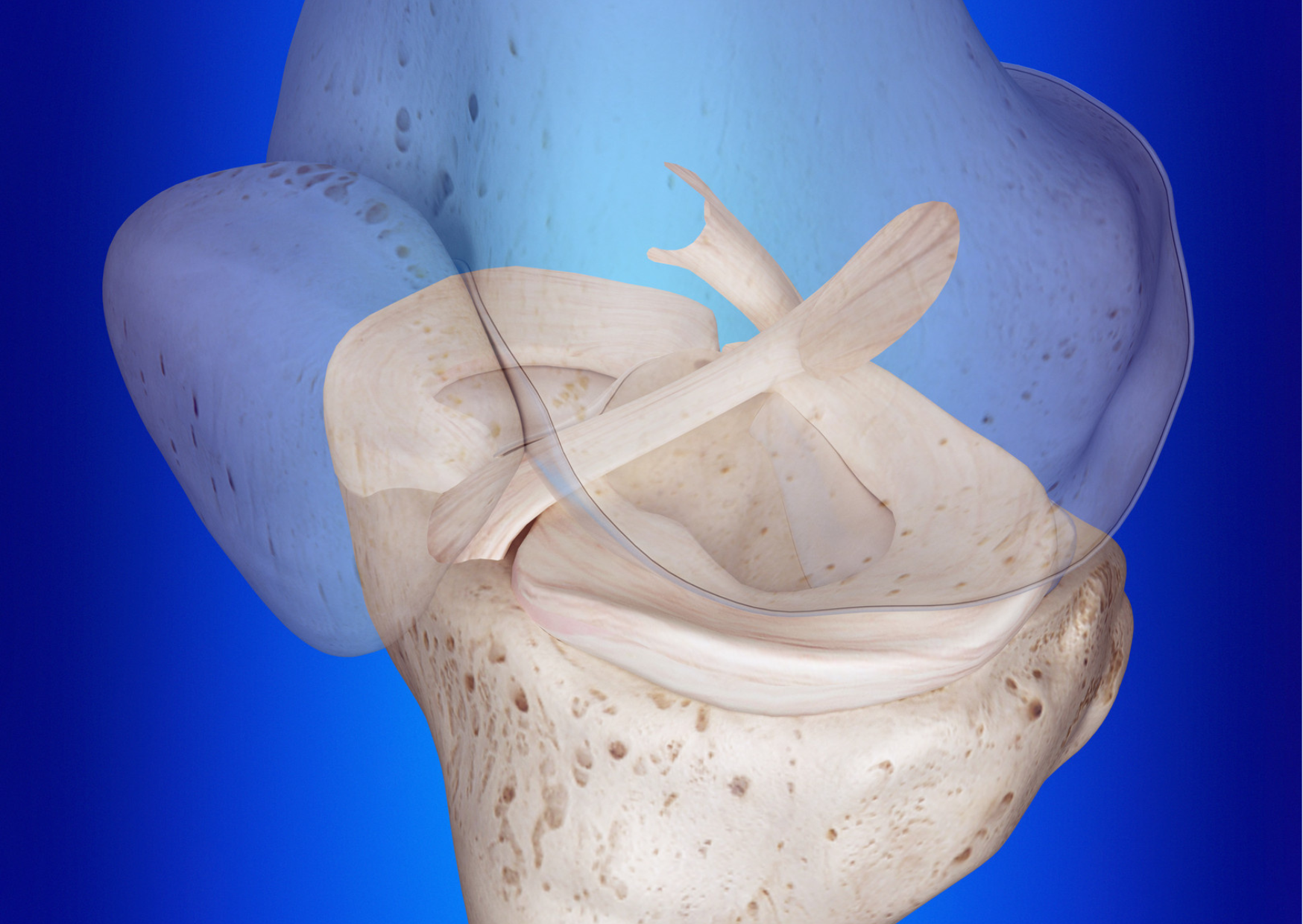

The image above shows the anterior cruciate ligament on the left and the posterior cruciate ligament on the right. Note how the cruciate ligaments cross centrally and emerge from opposite sides of the knee. This orientation means that specific elements of each ligament remain taught during varying degrees of knee flexion and knee extension. Knowing this anatomical and physiological information enables us to diagnose injury based on when we know each of these structures is most stressed. (eg a hyperextension injury would typically make us suspect PCL injury whereas internal rotation of the tibia (shin bone) on a relatively extended knee would make us suspicious of ACL tears.

PCL mechanism of injury

A typical Posterior cruciate ligament injury occurs when a posterior shunt of the tibia occurs relative to the femur. This is often described as a dashboard injury but can also occur when a flexed knee is hit directly from the front (eg in a rugby tackle around the shin bone) and the forces are transmitted posteriorly through the knee damaging the PCL. As mentioned above an alternative mechanism of injury would be during hyperextension or rotation. Although typically this is seen within sports injuries they can occur in non-sporting activity such as RTA.

As with ACL injury, it is likely that the knee presents as extremely swollen (Grade 2+ effusion) within the first 12-24 hours due to bleeding into the joint. The stability of the joint will need to be assessed. Cruciate ligament injuries usually result in significant swelling and this may need to be aspirated (removed with a needle) to improve pain and range of motion. You will be offered pain medicine to make the knee more comfortable.

They may present with a posterior sag sign

You can carry out a full assessment of the PCL stability with a posterior drawer test; see this video from FIFA on youtube https://youtu.be/b0ehvawVCK4

Once injury of the ligament is confirmed from a clinical or combined clinical and imaging assessment then a decision will be made on if surgery is required. In the case of surgery (dependant on the degree of laxity and if it is a complete tear) then the individual will follow the orthopaedic surgeon’s protocol. If the ligament injury isn’t complete (High Grade 2) then a period of conservative rehabilitation will begin and a Knee brace will be utilised to stabilise the healing structures.

There are a number of knee braces available but in the case of PCL injury, it will need to be a brace which results in an anterior or AP force to stop the tibia from sagging further and resultant lax or poor healing.

Types of braces suitable for these knee injuries include but are not limited to https://braceorthopaedic.co.uk/products/jack_pcl/ or https://www.ossur.com/en-gb/bracing-and-supports/knee/rebound-pcl . Make sure you get advice on guidance on effective use from your Physiotherapist, Sport and Exercise Medicine Consultant or Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon.

Collateral ligament injury

Knee ligament injury primarily affecting the ligaments on either side of the knee are known as collateral ligament injuries. If the injury is on the inner knee this would be a Medial collateral ligament or MCL injury and you can read more about them here. These knee ligament injuries typically occur during a block tackle or rotation, essentially when the knee is opened up with a valgus stress.

With grade 1 injury the athlete can typically continue but may present with a stiff and sore knee the day after, with Grade 2+ injury they are likely to feel unstable and need to stop the sport or activity. In these cases they be clinically assessed and placed in a brace; laxity can be picked up with the Valgus Stress Test as shown here.

If the injury site is on the outer knee then it is likely the person has injured the Lateral Collateral ligament, an LCL injury sometimes referred to as FCL or Fibular collateral ligament. These injuries can also occur during a block tackle or forced rotation when the feet stay planted; isolated LCL injuries are quite rare and will often involve other soft tissue structures on the outer side of the knee as discussed above in relation to PLC injury.

If higher grade injury is suspected the patient should be placed in a brace and further investigations undertaken. A Varus stress test can be carried out to check for laxity and pain.

Rehabilitation after knee ligament injury

Whether surgery is required or a conservative approach to rehabilitation is chosen as the pathway to recovery, it is vital this is carried out under the guidance of an expert.

A period of protection of the injured structures followed by muscle strengthening exercises for the muscles around the knee and the lower body and core in general will be carried out. Although the initial injury can be very different and the subsequent timescales vary hugely the main ligaments will eventually reach a point where rehab is about returning the athlete and patient back to everyday life or their sport.

You can read more about our approach to the management of knee injuries here and why every rehab is a unique journey here.

If you need more information about cruciate ligaments, collateral ligaments, knee pain, bone pain, knee instability or other sports injuries contact us here at R4P